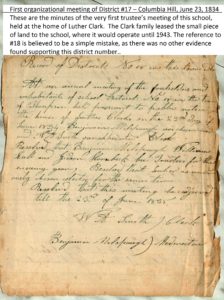

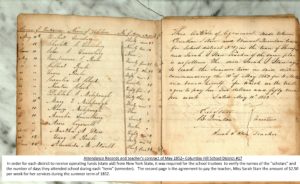

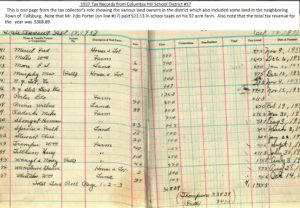

How did this system of one room schools take place?? At the end of the synopsis, I have included scans of actual documents from the Columbia Hill School records from the collection of Paul Lounsbury, that will illustrate and support various portions of the history as it affected this and the other schools.

The answer is quite lengthy and complex, as with anything dealing with State government, so, I have boiled the story down as follows:

In 1784, NYS passed legislation to create a system of “common schools.”

In 1812 a landmark law established a statewide system of common school districts and authorized distribution of interest from the Common School Fund.

Town and city officials were directed to lay out the districts; the voters in each district elected trustees to operate the school. State aid was distributed to those districts holding school at least three months a year, according to population aged 5-15. Revenue from the town/county property tax was used to match the state school aid. While the 1812 act authorized local authorities to establish common school districts, an 1814 amendment required them to do so. Yet, in spite of this, education was not completely “free” for families. An 1849 statute provided for a combination of state and local funding for tuition-free common schools.

The guarantee of a free primary and secondary education was embodied in the state Constitution in 1894: “The Legislature shall provide for the maintenance and support of a system of free common schools, wherein all the children of this State may be educated.”

-Origins of the High Schools. Beyond the “3 R’s” (readin’, ‘ritin’, ‘rithmetic) offered by the common schools, more advanced instruction was available in private high schools known as “academies” or “seminaries.” By the 1850s about 165 academies around the state provided secondary education (very few youths went on to college).

-School Aid Quota System. Between 1812 and 1851 state aid to schools came from two dedicated revenue sources, the Common School Fund (for common schools) and the Literature Fund (for academies). The fund’s return did not keep pace with the needs of the schools, and between 1851 and 1901 a modest statewide real property tax provided additional revenue for school aid.

During the 1920s state aid to public schools increased dramatically, from under 10 per cent to about 27 per cent of total costs. A new state aid formula was enacted in 1962, providing relatively more aid for less wealthy school districts, with a roughly even split between state and local financing for schools statewide.

State law has always provided for oversight of public schools. Between 1795 and 1856 elected town commissioners or superintendents of schools licensed teachers, distributed state aid, and compiled statistical reports. Locally-appointed County Superintendents of Schools oversaw the common school districts from 1841 to 1847. Their reports to Albany deplored the poor condition of the country schools. (A survey in 1842 found that most of them lacked outhouses and playgrounds.)

Transporting rural children to school became possible with the coming of automobiles, paved roads, and snow plows. Transportation of students in union free and central districts was required by a 1925 statute.

-Universal School Attendance. Attendance figures were used to calculate all or part of Regents’ aid to private academies starting in 1847. The advent of free public education in the 1860s provided the opportunity to promote, or to compel, regular attendance in the public schools.

-Average daily attendance was used to compute part of general school aid starting 1866, in the hope of encouraging attendance. An 1874 law required most children to attend school at least 70 days a year, but there was little means of enforcing this law. Growing public concern about child labor in factories and sweatshops helped persuade the Legislature to pass a strong compulsory attendance law in 1894. The law required children aged 8- 12 to attend the full school year of 130 days; employed children aged 13-14 had to attend at least 80 days. The school year was increased to 160 days in 1896, 180 days in 1913, and has not changed since.

-Centralizing the districts: The Cole-Rice Law of 1925 provided financial incentives for the formation of “central rural school districts,” first authorized by a 1914 statute. The generous 50 per cent transportation aid and 25 per cent building aid prompted a steady growth in the number of centralizations, especially during the economic depression of the 1930s. The Department’s bureau of rural education worked with the District Superintendents to promote centralization of rural schools, and developed a “master plan” for school consolidation. Statutes passed in the 1950s permitted consolidation of common school districts with smaller city districts, and by the 1960s centralization was essentially complete.

The following are images of the records that were preserved by the Lounsbury family, and passed down to committee member Paul Lounsbury:

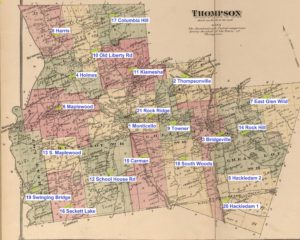

The newly appointed school district officials set out on the task of locating the population centers where a school should be located, appointed local trustees, and arranged for the actual construction of the school houses as shown on this map below: